How one program helps scientists and the public connect with the past

by Jeremy Weirich

Classroom Exploration of Oceans Virtual Teacher Worshop series, October 10, 2005

Introduction

Shipwrecks and submerged prehistoric landscapes are unique places containing a wealth of cultural, archaeological and environmental data. Historic shipwrecks acquaint us with the maritime cultures of the past, the builders, sailors, mariners, and traders who were the lifeblood of early shipping industries and storied naval conflicts of mighty sea powers. Their stories are often missing from the written record, but archaeology can give them a voice.

The U.S.’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Ocean Exploration (Ocean Exploration) investigates the oceans for the purpose of discovery and the advancement of knowledge of the marine physical, chemical, biological and archaeological environments by means of interdisciplinary expeditions to unknown, or poorly known, regions. Advancements made by this program, in collaboration with other government, academic and industry partners provide more opportunities for investigating maritime heritage resources – such as shipwrecks and submerged prehistoric landscapes.

This presentation will highlight a few recent exploratory projects sponsored by Ocean Exploration. Along the way, explorers have uncovered more opportunities, responsibilities and challenges with respect to resource management since we are finding maritime heritage sites faster, in deeper waters, and often in places where there are no management or enforcement authorities.

Ocean Exploration and Maritime Archaeology

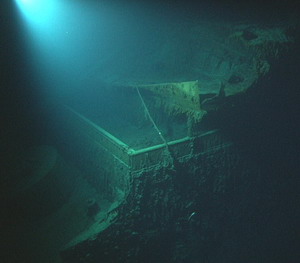

When one thinks of the quintessential ocean exploration expedition, the mind may conjure images of deep-sea environments and futuristic robots visiting strange, uncharted reaches of the ocean. With 90% of our world’s ocean still unexplored, it is not uncommon now for NOAA and its partners to research strange new environments with innovative underwater technology. Exploring lost deep-sea shipwrecks is especially intriguing, knowing many of these vessels were last seen generations ago, gracefully carving through waves and sea spray. Today, the eerie, dark ocean adds to the ghostly atmosphere where these vessels now quietly rest, holding secrets to our maritime past.

Researchers visiting deep wrecks need to bring everything – including their own light. In this haunting image, Titanic 's bow is a stage for shadows and twisted steel. (Courtesy of NOAA/IFE/URI)

Although NOAA sponsors archaeological expeditions to far-reaching locations, maritime researchers also recognize there is still much to learn close to home. Every year there are new discoveries of shipwrecks right off our docks, in our rivers and along our beaches, all worthy of further research and new understanding.

Ocean Exploration researches both familiar and unknown environments, and each year sponsors a wide variety of archaeological expeditions far and near. These are collaborative expeditions to discover new submerged cultural resources and to share knowledge about our maritime heritage. Projects may include:

- Any shipwrecks or historic aircraft within U.S. state and federal waters (coastal, lakes, Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ), etc)

- U.S.-flag ships sunk throughout the world

- Submerged, prehistoric landscapes

- Historical structures directly pertaining to maritime heritage

- Shipwrecks holding a unique place in human history, wherever they may be found.

With a focus on the initial phases of marine archaeology – discovery, investigation and inventory – Ocean Exploration equips maritime heritage researchers with vessel time, advanced technologies and financial support to a degree not readily available a few years ago. The goal is to expand our knowledge of shipwreck science and maritime heritage. Through Web site offerings, news releases and other means, Ocean Exploration tries to bring the public along too, sharing new discoveries as they happen whenever possible.

Recent Archaeological Exploration Expeditions

Since Ocean Exploration officially began in 2001, the program has sponsored many maritime archaeology projects. To discuss each would take more time than this presentation allows, but there are a few expeditions worth highlighting. They open the door to our imaginations and expand the limits of technology, but they also deliver new experiences we had not expected. Sometimes when we explore the past, we discover new ways to look at the future.

Ancient Mariners of the Black Sea

Maritime archaeology is only one category of exploration projects conducted annually, and only a few of those are considered full-scale expeditions. These are usually large field projects where scientists are supplied with vessel time and funds to complete their research. A recent example of a large-scale project was the 2003 Black Sea Expedition where Dr. Robert Ballard’s Institute for Exploration (IFE) explored the stagnant depths of the Black Sea to locate and document ancient shipwrecks and to search for indications of man-made settlements.

The Black Sea is a unique basin in that there is little or no oxygen below a few hundred meters. Although there is plenty of fresh water entering from rivers, the only area where water drains is the relatively shallow opening of the Bosporus Strait. This poor circulation is limited mostly to surface currents, and creates a moribund bottom layer of cold, anoxic water. Aside from anaerobic bacteria, the bottom is barren of life. There are no wood-boring worms, common in the open ocean, so this environment is ideal for preserving organic matter, such as the ancient wooden shipwrecks.

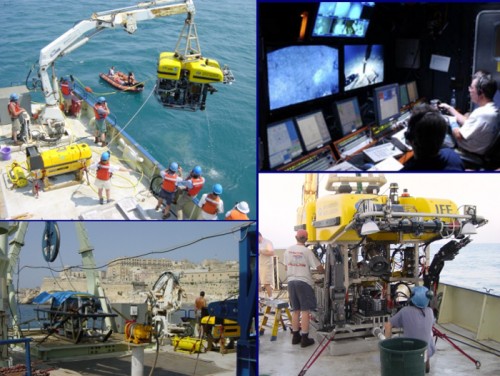

Using information from previous expeditions, researchers in 2003 decided to explore four possible shipwreck sites located off the coast of Sinop, Turkey. Sailing aboard the science ship R/V Knorr, the team used a new ROV (remotely operated vehicle), Hercules, to acquire archaeological data. Hercules was specially designed by marine engineers and maritime archaeologists to conduct underwater archaeological surveys. Its equipment included advanced high-definition cameras, sonar mapping instruments and a combination vacuum/water jet system for removing surface sediments. It also had two manipulators, or robotic arms, one with force-feed back capabilities, meaning that when using the arm to grab something at the site, the ROV pilot feels the sensation of pressure in the controls as if the object was held directly in the pilot’s hand.

Collage of images from the 2003 Black Sea expedition showing (clockwise from upper left): Hercules lowered into the water; control van where pilots and navigators sit (courtesy of IFE); a front view of Hercules; Argus on the fantail, as the R/V Knorr leaves Malta for the Black Sea.

This unique vehicle worked in tandem with the ROV Argus, which served as a lighting and imaging platform. Operated by a team of skilled pilots and engineers, and guided by archaeologists, the two robots served as ideal underwater workers for investigating these deep sites.

Three of the four shipwrecks were not deep enough to be in the anoxic layer. Their wood and other material had long since decomposed, and all that remained were piles of clay amphorae. Theses large clay containers once held any number of goods for transport in the ancient world. Their shape and composition are unique to the different coastal communities that created them, indicating the port where the vessel last took on cargo. This tells archaeologists more about ancient commerce, and according to these amphorae, these wrecks last left Sinop.

The fourth shipwreck, deep in the anoxic layer, was completely different. Although dating back to the Fifth Century, this shipwreck was so well preserved it had the appearance of a ship that sank only a few years ago. The ship’s mast was still standing 35 feet high, with small piece of leather still latched at the top where the rigging once attached. Tool marks left behind by an adz were still evident where ancient shipwrights crafted the vessel long ago. The Black Sea’s anoxic waters had kept the wreck a well-preserved time capsule, as predicted.

A clear sign the ship had been down there for many years was the centuries of sedimentation that accumulated in and around the site, burying it up past the side planks. After mapping the site, Hercules settled down next to the wreck to remove some of the surface sediments, which were the color and consistency of Tiramisu – soft and goopy. Though superficial, the test excavation revealed perfectly preserved planking, and a boatload of amphora.

Collage of artifact and shipwreck images from the 2003 Black Sea expedition showing (clockwise from upper left): Dennis Piechota prepares an amphora for conservation; Hercules' manipulator arm brushes away years of sedimentation from a wood post, just like an archaeologist; Dennis Piechota and Todd Gregory, an ROV pilot, examine a piece of amphora during conservation; well-preserved wood frames, complete with tool marks. (Underwater images courtesy of IFE.)

One amphora later recovered still had sealing wax around its opening, which helped to cap the contents. Careful examination of the side of the jar also revealed a thumbprint left by the original craftsman. Seeing something like that – something so casual and delicate, yet not worn away by time – can be surprisingly powerful. An ancient thumbprint may not tell much about past cultures, but noticing it instantly connects your imagination to someone who worked and lived 1500 years ago.

This site produced finer details than did other wrecks the team investigated. It provided a rare, intimate glimpse into ancient ship construction, and, together with its cargo and other artifacts, told archaeologists more about the people who once sailed, traded and lived long ago. It is anticipated that a full excavation of the site could yield more well-preserved artifacts.

The Gulf of Mexico and Shipwrecks of World War II

Ocean Exploration lends itself easily to partnerships nationally and internationally, drawing upon unique technologies, talented researchers, and innovative marine programs. To best serve the shared goal of protecting historically important maritime sites, and given the relatively small maritime heritage community in the U.S., the program collaborates with federal partners regularly on resource issues, namely the National Park Service, the Minerals Management Service (MMS) and the Naval Historical Center.

A recent example of exploration project highlighting government and industry partnership was the 2003 expedition conducted aboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown to document the wreck of the German submarine U-166 located in the Gulf of Mexico.

First discovered in 2001 by C&C Technologies, Inc during a pipeline survey, the remains of the then unknown U-boat were an initial mystery to C&C archaeologists Dan Warren and Rob Church who reviewed the sonar data. Having worked with data from a number of remote sensing surveys, the two can easily recognize a shipwreck target within any sonar dataset. They are also quite familiar with the maritime history of the Gulf of Mexico, but according to historical records, there was not supposed to be a wreck in that area, especially a target that looked very much like a submarine. What was it?

During World War II, 24 German U-boats operated in the Gulf of Mexico, sinking 56 merchant vessels in one year with only one U-boat lost; the U-166. The submarine was assigned to the Gulf in July of 1942 to lay mines near the mouth of the Mississippi River, and to patrol shipping lanes to hunt merchant shipping. On July 30th, the passenger freighter Robert E. Lee and her naval escort PC-566 were transiting across the Gulf en route to New Orleans. That afternoon, the Robert E. Lee came into the sights of the U-166 , and was struck by a torpedo on the starboard side.

The conning tower and forward deck gun of the U-166 , viewed from the foredeck as the boat was transiting the Kiel Canal between the Baltic and North Seas. (Image courtesy of the PAST Foundation and the D-Day Museum, New Orleans.)

As the Robert E. Lee began to sink, PC-566 rushed in and began depth charging the area where the U-boat was located. Although the crew was confident they sank the submarine, the ship was not given official credit for the sinking. Adding to the confusion was a historical document indicating that a U.S. Coast Guard seaplane, which reported bombing a U-boat two days later, 140 miles farther west, was given credit for sinking the U-166 .

The true account of what happened to the U-166 would not be written for nearly sixty years until the 2003 expedition to explore the site led by Warren and Church. Partners from Ocean Exploration, MMS, Sonsub International, Sonardyne, Droycon Bioconcepts, Inc and the PAST Foundation joined to offer various expertise and technology to investigate the mysterious of wreck site. Using an industry ROV and special positioning equipment to accurately survey the area, the expedition team located the broken U-166 lying upright at a depth of 5000 feet.

The bow was separated from the rest of the boat by several hundred meters. Between the two sections was a debris field with many different artifacts. Everything was accurately mapped and imaged. The main portion of the sub was in relatively good condition. The team could clearly identify the two large deck guns, and even see intricate features in the conning tower. Although located in a cold, deep environment, which was great for preservation, the wooden decks had been eaten ways years ago by marine animals, exposing the twisting pipes, dormant machinery and skeletal hull. Aside from a few sea anemones and small rusticles (bacterial communities that feed off the metal from shipwrecks to produce rusty, stalactite-like features), there was very little marine growth or corrosion on the wreck.

- Movie clip: U166_Deck_to_tower.wmv

Movie note: View of a Sonsub ROV as it flies over the wreck of the U-166 submarine, moving from the forward gun to the conning tower. (Courtesy of C&C Technologies, Inc.)

With additional historical information, this investigation confirmed that the naval escort PC-566 actually did sink the U-166 on that July afternoon in 1942. The U.S. Coast Guard seaplane had apparently depth-charged a different U-boat, the U-171 , which was able to escape with only minor damage. We know this because the U-171 had been prowling in that area, and later reported its narrow encounter with the plane.

This ocean expedition arguably represented the largest and most significant contribution of a deep-sea industry ROV to the field of maritime archaeology, and it led to a more comprehensive, 18-day research expedition in 2004 to investigate several other World War II casualties of U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico. Ocean Exploration and MMS sponsored C & C Technologies, Inc. to archaeologically and ecologically assess seven vessels sunk by U-boats. Since these sites ranged in depths from 280 ft to 6,500 ft, they offered biologists a unique opportunity to study the artificial reef effect in differing ecological niches. This information will be used to help determine the corrosion potential of deep-sea oil drilling rigs and production platforms. These structures will be decommissioned in the coming years, and this study will help us better understand what might happen to them and whether they will be good candidates for artificial reefs 60 years from now.

Locating the Russian-American Trader Kad’yak

“Surveys of opportunity” are a type of expedition in which Ocean Exploration takes advantage of gaps in the schedules of ocean-going, research vessels either owned by NOAA or chartered by the program. Since shipwrecks are ubiquitous, it is often fairly easy to find marine archaeologists interested in investigating submerged resources in the same region where one of our vessels is working.

Some “surveys of opportunity” take just a few hours as a vessel investigates a specific area while transiting from one expedition to another. The most successful “transit projects” have been organized aboard NOAA’s fleet of hydrographic survey vessels, operated by NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey. These specially designed survey vessels are outfitted to chart the U.S. coastline systematically for the purpose of safe navigation. With high-tech, remote sensing equipment already on board and expert staff to operate it, these ships are ideal for investigating lost wrecks.

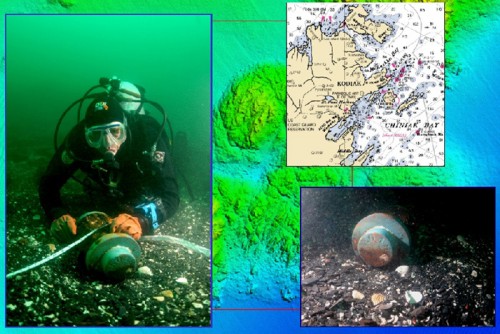

Last year, the NOAA Ship Rainier, one of NOAA’s hydrographic survey vessels assisted an Ocean Exploration-sponsored project to use sonar technology to map the suspected wreck site of the Russo-American trader, Kad’yak located near Kodiak, Alaska.

The NOAA Ship Rainier with her six survey launches off the coast of Alaska. (Courtesy of NOAA Office of Coast Survey.)

Kad’yak sailed in the Russian American Company fleet in the final years before the United States purchase of Alaska in 1867. On her final voyage, the Kad’yak was transporting a cargo of ice to San Francisco. Shortly after leaving Kodiak harbor in March 1860, the vessel hit an uncharted rock and quickly filled with water, forcing the crew to abandon ship. However, since the ship was filled with a cargo of ice, the Kad’yak stayed afloat for three days before sinking in nearby Icon Bay.

The mast of the ship protruded above the water with a single yard forming the shape of a cross, visible from the shrine of Father Herman on the shore of Spruce Island. According to legend, the Kad’yak’s captain failed to pay proper homage to the monk in Kodiak Cathedral before his departure from the island. At the time, many locals attributed the Kad’yak’s wrecking to this secular snub.

After conducting historical research, Dr. Bradley Stevens of the NOAA Kodiak Fisheries Research Center, discovered what was thought to be the Kad’yak wreck in July 2003. In 2004, researchers from the Maritime Studies Program at East Carolina University (ECU) led by archaeologist Frank Cantelas, worked with Dr. Stevens, other scientists from the NOAA Kodiak Fisheries Research Center, and Alaska’s State Archaeologist to confirm the identity of the wreck and complete an archaeological documentation of the Kad’yak shipwreck site.

Today, the Kad’yak lies in 80 feet of water between two submerged ridges. Wood eating marine organisms and stormy seas, have contributed to the vessel’s deterioration. Cannon, anchors, a windlass, portions of the rudder and other iron and bronze artifacts lay scatted on the bottom where they fell as the ship deteriorated. A portion of the wooden hull remains only because it was buried under the sand.

Archaeological diver with an artifact from the wreck of the Kad

While that project was underway, the NOAA Ship Rainier coincidently docked in Kodiak to take on supplies. The ship’s officers knew about the Kad’yak project having previously received a request from Ocean Exploration to survey the wreck site. They were not aware the project was underway and very nearby. As is often the case in small towns, the two crews met up and exchanged information. A week later, the Rainier surveyed the site using high-resolution multibeam sonar system resulting in an extremely accurate and detailed map of the area.

Collaborations like this between NOAA hydrographers and marine archaeologists yield valuable cultural data, and improved the way maritime heritage researchers design their own remote sensing surveys. It is also a great example of how government programs try to maximize resources.

What happens to shipwrecks once they are found?

As underwater technology advances and greater numbers of submerged resources are found, explorers must consider the future of newly discovered shipwrecks. Unlike other ocean expeditions that investigate natural resources, projects involving maritime heritage sites offer unique challenges in that cultural sites are susceptible to illegal salvage and looting after they are discovered.

In contrast to some natural resources, shipwrecks are non-renewable; once a site or artifact is damaged or lost, it is gone forever. Removing artifacts from a shipwreck without conducting a proper archaeological or site formation analysis, robs the site of its historic integrity, and may adversely affect any marine ecology communities using the site as a habitat.

Even though Ocean Exploration does not directly manage cultural resources, the program recognizes that an appropriate investigation of cultural resources may require ongoing management long after discoveries are made. To help meet this challenge, the program directly supports cultural resource management programs in other part of NOAA, and in state, federal and foreign government agencies. For example, representatives from the Turkish government participated in the 2003 Black Sea Expedition and received all the conserved artifacts that were recovered. The ultimate goal of these partnerships is to ensure that any discoveries – whether coastal or in the deep ocean – are not just reported, but are receiwed to determine whether a long term management plan is needed.

The program involves resource managers in the initial project design, at-sea operations and subsequent data distribution. Contacts with local citizens ensure that the public is involved when possible. Given sensitivities about making public, and thus placing at risk specific site location information, Ocean Exploration allows local managers to determine what information is appropriate to release to the general community.

A memorable experience I had engaging a local community on maritime heritage happened in Kodiak in preparation for the Kad’yak project. As part of a larger trip to Alaska, Dr. Tim Runyan, Frank Cantelas (both from ECU), Jeff Gray (NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program) and I traveled to Kodiak to engage the community through meetings with various community members in preparation for the coming project. An additional goal was to reinforce their commitment towards preservation of their maritime heritage, something that was recently challenged by outside illegal salvagers pillaging wrecks off their coast.

As it turned out, we found that Kodiak’s interest in their maritime heritage remained strong, and the community was united in support of the Kad’yak project. It seemed everyone in the town came out to speak with us. During that visit, we also secured arrangement for the project’s research vessel, the Big Valley , captained by Gary Edwards. He had helped with NOAA projects in the past, and offered to provide his boat, a local crabber, at a very good rate for the coming summer project. His vessel worked out wonderfully, and the amenities that came with it were surprise bonus for the ECU and NOAA scientists making the cold diving a little more comfortable.

The F/V Big Valley on station at the Kad'yak wreck site, with an inset of the captain Gary Edward and maritime professor Dr. Tim Runyan on the vessel's bridge. (Courtesy of Tane Casserly, NOAA/NMSP.)

I am reminded that even though most of Ocean Exploration’s projects take place in the deep, unexplored crevasses of the far-reaching oceans, many of the program’s maritime archaeology projects directly affect local communities. Some of these communities are small and filled with people who are often surprised and gracious at federal interest. Despite some initial reservations, they appreciate the support we provide and quickly open up. Members of these small communities have always said the same thing to me when I leave: “Thank you for coming here to help us out.” Request that I one day return also come with invitations to stay in their homes, not hotels.

Small coastal communities, such as Kodiak, Alaska – a hard-nosed fishing village with great people and five museums dedicated to their heritage – have much in common in terms of their bond with the past, family-like support for the ones around them, and deep concern for the future. That is why maritime heritage is more than just shipwrecks – it’s about landscapes, lifestyles, traditions and people. Important things these folks live with constantly.

Bringing the Public Along

A minimum 10% of Ocean Exploration’s annual budget supports education and outreach. Formal lesson plans are correlated with National Science Education Standards to help bring a number of expeditions into the classroom. Several maritime archaeology-focused projects have corresponding lesson plans such as the Steamship Portland expedition and Return to Titanic .

In some cases Ocean Exploration-sponsored expeditions also provide a telepresence, directly linking researchers to classrooms and public venues. At times, this can be as basic as making a phone call to a school using a special satellite phone from the research vessel to shore. Other telepresence projects, such as the 2003 Black Sea Expedition, and later the Return to Titanic , are more involved.

For the 2003 Black Sea expedition, the Institute for Exploration and the Immersion Institute used an innovative telecommunications system to transmit still and video images via satellite to the U.S. They were then distributed live throughout the world on Internet and Internet II networks. This allowed scientists and archaeologists to answer questions directly from children and adults from all over the country even though the research ship was working in the middle of the ocean thousands of miles away.

Shown here is an example lesson plan from the Return to Titanic expedition and the cover of Ocean Exploration curriculum. The lower right corner shows a live broadcast from the deck of the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown

Some maritime archaeology projects and expeditions are supported by Web sites updated regularly though daily logs written by various researchers actively involved in the expedition. The PAST Foundation arranged this for the U-166 and Gulf of Mexico shipwreck expeditions. Their interactive website provided daily text and ROV still photos, and two- to three-minute streaming video pieces were offered every other day. Award-winning filmmaker Dr. Dennis Aig, professor of media and theatre arts at Montana State University, Bozeman, will also produced a documentary of the second expedition.

Outreach is the essential mechanism to educate the public about the significance of our heritage, both culturally and ecologically, which is inseparable. With that knowledge, and the realization that when these wreck sites are gone, they are gone forever, the local community must take on a more preservationist point of view, opting to take pictures rather than artifacts.

This change is similar to the conservation movement that evolved from coral reef initiatives. Dive charters to wreck sites grow in numbers, responsible fishing over wreck sites improves, and the attraction of maritime heritage material born out of research and residing in museum exhibits or other presentations, attracting tourists and adding to the community’s commerce base.

The Future of Marine Archaeology and Exploration

In the coming years, NOAA will continue to work with coastal and Great Lakes communities to map and explore maritime resources within their jurisdictions, and help to develop appropriate management schemes for researching and addressing their resources. Ocean Exploration has established conduits of communication, not only from one government agency to the next, but within all aspects of the community.

As our research, communication and outreach expand, the U.S. will increase momentum toward locating, understanding, protecting and appreciating our maritime heritage. Providing local communities with information about submerged cultural resources will foster an appreciation that will protect and preserve our history and our marine environment for the coming generations.

In the meantime, there are still plenty of shipwrecks out there to discover and explore – in both deep and shallow environments. More shipwrecks than I will ever be able to investigate, and certainly enough for your students to study. By the time some of your students sail the ocean as marine archaeologists or other marine scientist, it will be common for autonomous underwater vehicles (unmanned underwater robots scooting around with no tethers) to pop up to the surface periodically to send images and data to a satellite and then to your computer screen in schools and at home. “What’s the next amazing shipwreck?” “How will new technology change the way we write history?” Your students are the ones who hold the answers to these questions, not the scientists exploring today.

Leave a Reply